by Piero Bernocchi

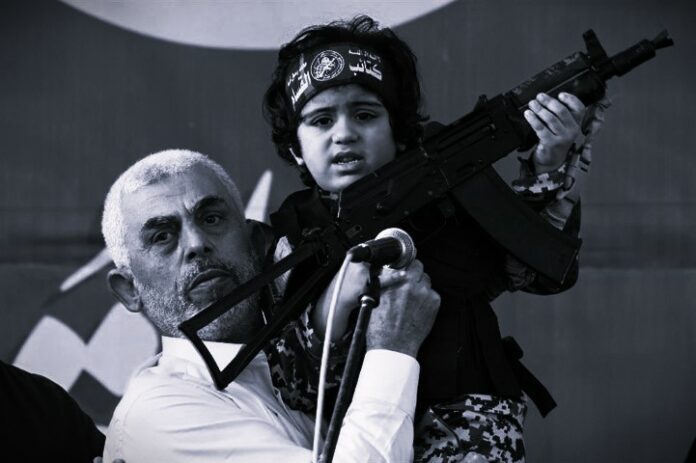

Leon de Winter is a Dutch writer who, in addition to his books, maintains a constant socio-political presence with articles published in various European newspapers and magazines. Regarding Sinwar, he wrote in an article in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, a Swiss newspaper with almost three centuries of history: “Yahya Sinwar had found the weapon with which to defeat the Jews and manipulate the world: the death of his own people. He invites the Jews to kill his people, and the Israelis cannot escape the fight against Hamas. Sinwar knew how to exhaust the Jews, blackmail them, and turn them against each other.” Indeed, Sinwar’s strategic plan, culminating in the horrific massacre of October 7th, had its own tragic strategic grandeur. However, contrary to de Winter’s interpretation, it was undone by a series of mistakes and misjudgments regarding unrealized possibilities, committed by the Hamas leader, which proved tragic and fatal for the Palestinian people as well as for Sinwar himself. This chain of erroneous evaluations, which I will try to analyze and comment on here.

The Failure to Involve the Entire Islamic World in a Direct Attack on Israel

For months now, credible documentation from various reliable sources has circulated explaining how the massacre of October 7th was planned—perhaps with not identical details—likely for at least a couple of years and had been postponed multiple times, waiting for more favorable general scenarios. There is broad agreement among insiders about the reasons, at least two dominant ones, that ultimately led Sinwar and Gaza’s internal leadership to choose the date of October 7th. I will return to the second reason later, but here I will focus on what I consider the most relevant and decisive: the absolute necessity to thwart the expansion of the Abraham Accords (which normalized relations between Israel, the United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain) with the inclusion of Saudi Arabia and possibly Qatar, and with the formation of a very influential bloc of Sunni countries led by the most powerful nation of the Islamist world, Saudi Arabia—a great and historic adversary of Shiite Iran since the rise of the Ayatollahs to power in Tehran.

One of Sinwar’s strategic insights was to wedge himself into this emerging alignment, favorable to the normalization of relations with Israel, and at the same time, to cement the anomaly of a close relationship, with consequent copious funding and military support, between an organization of extreme Sunni radicalism like Hamas and the Iranian stronghold of the Shiite world. This was an absolute anomaly just a few years earlier when Sunnis and Shiites were slaughtering each other daily across the Islamic world, with casualties far exceeding those in conflicts with Christians, “Westerners,” and Jews. This anomaly may have been the most remarkable and potentially capable of opening new and unexpected scenarios for the monumental and seemingly insane plans for the total destruction of Israel.

However, to activate such a scenario, an action was needed that was so terrifying, shocking, and merciless, manifesting itself in the most barbaric forms possible, that it would provoke an equally savage, brutal, and massacring response from the Netanyahu government. Sinwar counted on the colossal humiliation imposed on the entire Israeli military apparatus and on the global disgrace inflicted on an ultra-ambitious, unscrupulous leader like Netanyahu, who, in his desire to erase the PNA and Fatah from the scene, had been deceived by Sinwar and had long facilitated his rise to power in Gaza, giving him a dominant position over all Palestinians.

Consequently, I believe the horrors of October 7th were not due to spontaneous barbarism or an uncontrolled orgy of vengeance by the thousands of armed Palestinians involved, but rather were planned and intended by Sinwar and his followers (and for this reason, documented and exhibited with the most gruesome videos, photos, and audio recordings) precisely to render a merely “moderate” response from the Israeli government unrealistic and, in fact, impossible. Sinwar’s gamble, cynical and merciless but not crazy in principle and potentially successful, was to push Netanyahu to attack Gaza with an unprecedented level of destructive force, causing the highest possible number of civilian casualties. Sinwar had repeatedly admitted, without embarrassment, that he was willing to sacrifice an exorbitant number of his own unarmed compatriots to create the conditions for Israel’s defeat and destruction.

The aim was to provoke both widespread global indignation against Israel (and, more generally, against the presence of a Jewish state in Palestine, to be liberated “from the river to the sea”) and to push the entire Islamic world, both Sunni and Shiite, to militarily intervene, contributing decisively to Israel’s destruction. Despite my political, ideological, cultural, and moral aversion to holy war Islamism, dictatorial regimes like the horrific Iranian theocracy, and obscurantist, reactionary, ultra-misogynistic, and homophobic organizations like Hamas and Hezbollah, I cannot deny that this strategic plan had, at least in potential, what I called a tragic grandeur. In reality, this plan had indeed achieved its first objective: to provoke a vast wave of international outrage, even in previously unsuspected quarters, which quickly set aside the horrors of October 7th (often celebrated as a “redemption” for the Palestinian people after decades of oppression and humiliation, or even as “the beginning of the Palestinian Revolution”) to mobilize in an almost permanent protest against the ongoing massacre in Gaza, where Hamas militants killed by the Israeli army were accompanied almost daily by an equally large number of civilian casualties, with no distinction made between men, women, and children.

However, what did not happen—revealing itself as the main weakness of this highly ambitious strategy and Sinwar’s greatest miscalculation, along with those who shared his approach—was the general failure to involve the entire Islamic world, both Sunni and Shia, in a frontal assault on Israel. In hindsight, Sinwar demonstrated a surprising lack of understanding of the diverse and ambiguous complexity of this world. (As we will see later, Sinwar made similar and equally fatal errors of judgment—both for himself and for the Palestinians—in his analysis of Israeli society and the prevailing psychology among Israel’s Jews.)

It is astonishing, to begin with, that Hamas’s undisputed leader truly believed the bombastic war proclamations and the calls for the destruction of the ‘Zionist entity’ (as the Iranian theocratic dictators like to refer to Israel, refusing to even name it out of utmost disdain) from two mass rhetoricians and crowd-enchanters like Khamenei and Nasrallah. It is surprising that such a keen observer of every nuance in the thinking of Islamist radicalism could actually believe that the theocratic regime and Hezbollah would be willing to jeopardize their power and dominance in their respective controlled countries—Iran and Lebanon—and even risk the survival of their regimes, to join Hamas in a direct confrontation with Israel. They were well aware of their military inferiority, as well as the fragility of their internal rule, faced with two societies that are largely hostile: one in open revolt, as seen in Iran over the last two years, or subdued but non-compliant and non-collaborative like the Lebanese one, which has been unable to prevent the gradual domination of the Shiite minority over the country but fundamentally hopes for its possible military downfall.

In truth, in the behavior of almost all Arab countries and Iran toward the Palestinian tragedy, there has always been a deep instrumentalism that Sinwar and his associates should have been well aware of. After the Arab League’s failed attempts to militarily defeat Israel and expel the Jewish community from Palestine, most of the surrounding Arab countries have cynically used the Palestinian people and their struggle only to create as many difficulties as possible for Israel, to keep it under constant pressure, and to activate widespread international solidarity against the ‘Zionist entity.’ Yet this cynical and instrumental plan was never accompanied by genuine solidarity with the Palestinian people, neither in terms of significant material aid nor in the dignified reception of refugees, at least on a level consistent with the thunderous proclamations of the time. Imagine Hezbollah and the Iranian theocracy seriously challenging Israel in open, unmediated military confrontation, with the realistic possibility of not only being overwhelmed on the battlefield but also allowing widespread internal opposition to finally settle the score with their intolerable decades-long domination.

But Sinwar made another misjudgment, just as inexplicable for someone who, over many years, had had the opportunity to study closely, with maximum awareness of contacts and links, the complex, convoluted, ambiguous, and changing relations between the various Islamic states and communities in the Middle East. The Hamas leader seems to have taken seriously—and vastly overestimated—the deep bond he managed to establish, since he was still in Israeli prisons (where he was able to bribe prison guards, thus enabling him to communicate freely not only with his ‘subordinates’ in Gaza but even with the Iranian regime) as early as 2011, with the ayatollahs’ regime. Certainly, the anomaly of such a close, demanding, and unprecedented alliance between Sunnis and Shias, usually in permanent war against each other for centuries, may have misled Sinwar’s perceptions, to the point of mistaking a tactical agreement (very useful for Iran to sideline the project of a vast part of the Sunni world to normalize relations with Israel in the name of common economic interests) for a general and permanent strategic collaboration. But the majority of the Sunni world never digested the almost ‘intimate’ relationship between the militant Sunni Palestinian faction and Iran, let alone the great power acquired by Hezbollah, another standard-bearer of the Shia minority and also a close ally of Hamas. How alive this hostility was, despite the commonly broadcasted support for the Palestinians during the Gaza massacres, was openly visible in the celebrations in many Sunni Arab countries at the news of Nasrallah’s death, while at the same time, the killing of Sinwar hardly seems to have provoked great waves of solidarity and mourning in these countries.

Sinwar’s Miscalculations Regarding the Current Jewish Population in Israel

Though less striking, Sinwar’s second catastrophic miscalculation had equally disruptive effects on the monumental strategic project aimed at bringing Israel to its knees: the Hamas leader demonstrated another severe failure in social and political analysis, even more puzzling given how much time he had had to study Israeli society in detail, having even spent a long time within its prisons. On this point, the second part of De Winter’s comment, quoted at the beginning (‘Sinwar knew how to wear down the Jews, blackmail them, and pit them against each other‘), has proven to be flawed. Sinwar believed he knew ‘how to wear down the Jews,’ but he was likely accounting for the old Jews, not the reality that goes far beyond old Zionism: the Jewish people of Israel today. Indeed, at least on paper, the Hamas leader was not wrong in considering favorable, for the brutal invasion of October 7, the deep division in Israeli society caused by the reactionary and ultra-authoritarian domestic policies of the Netanyahu government, dominated, or at least strongly influenced, by the extreme right, theocratic and racist forces, intent on conceding nothing, and indeed taking even more away from the Palestinians. The internal conflict within the Israeli community, before October 7, had indeed reached unprecedented intensity, causing divisions, conflicts, and waves of hatred that Israel had never known within the Jewish world, even jeopardizing the government’s very survival. And, highly relevant to the success of Sinwar/Hamas’s strategic plan, this division had reached the military structure—the army, the intelligence services, and the entire Israeli combat, defense, and offensive apparatus, which appeared equally torn and divided.

What Sinwar failed to calculate, predicting instead the exact opposite of what ultimately happened, concerned the effect of the terrifying and barbaric pogrom carried out against the communities near the Strip on the entire Israeli population, which suddenly found itself defenseless and vulnerable, and in general on the political and military world of the country. In a ‘normal’ country, with a ‘normal’ population and a ‘normal’ leader, Sinwar’s predictions would probably have come true: such a shocking attack, able to expose the fragility of the containment system against sectors of Islamist extremism that consider death in battle against ‘infidels’ a glorious event, would have exacerbated internal divisions to the point of widespread social rupture and the paralysis of political and military institutions. But Jewish Israeli society is not ‘normal,’ that is, it cannot be reduced to the norm of any Western society that has not had to endure centuries—indeed millennia—of oppression, pogroms, constant persecutions, countless massacres, and subjugations, culminating in the monstrous Nazi Holocaust. The image of the Jewish sacrificial lamb, unable to react and a victim of any established power, has been replaced in just a few decades by that of the fierce and ruthless Jewish fighter, with a military, warlike, but also investigative apparatus of the highest level, immersed in a country that, since its inception, feels besieged and, in particular circumstances, accepts that anything, including atrocities, may be done for the survival of Israel.

Thus, October 7 provoked the exact opposite of what Sinwar’s strategy envisioned: the gradual unification of society around the only leader willing to do whatever it takes, no horror excluded, to crush Hamas (and subsequently Hezbollah, leading up to a direct confrontation with Iran if necessary). Even accounting for a massive number of civilian casualties, adults and children alike—whom Hamas thought it could use as human shields to protect itself from the planned extermination of their militants—day by day, a discredited, corrupt, ultra-authoritarian leader, openly opposed by the moderately democratic and secular components (which still exist in Israel and had, for over a year, marginalized the prime minister, coming close to his ousting), has managed to prevail and silence all opposition. Then, the chain of ‘high-profile’ assassinations—of Haniyeh, Nasrallah, and even Sinwar, under conditions reminiscent of the most vivid fantasies of a movie screenwriter—has not only rehabilitated the shocking failure of the intelligence services on October 7 but has also convinced a significant portion of Netanyahu’s opponents that the strategy of responding to the October 7 horror with terror multiplied ten- or twenty-fold, disregarding any ‘international conventions,’ is currently the most effective approach, at least in the here and now, for defending Israel. In short, the exact opposite of what Sinwar intended to achieve.

The flawed defensive shields of international protest and Israeli hostages

It is undeniable that at least one of Sinwar’s strategies has achieved a clear result, which was one of the main objectives of the massacre on October 7: to create a wave of hostility towards Netanyahu’s government and, more generally, against Israel on an international level, while simultaneously generating a strong current of sympathy and support for the Palestinians and for Hamas. However, even from this perspective, such a strategy, although powerful on paper, was accompanied by glaring miscalculations that led to its overall failure. This wave of aversion towards Israel and sympathy for Palestinians and Hamas had no influence whatsoever on Netanyahu’s government or the course of the war in Gaza. On the contrary, in some ways, it further embittered the actions of a government and military apparatus that had already demonstrated abundant ruthlessness and lack of scruples. As the campaign of hatred towards Israel grew internationally, the Israeli leader had an easy time arguing that it was not merely a product of solidarity with the Palestinians but also included a more general anti-Jewish sentiment (the term “antisemitism” is incorrect since Semitic origins are shared by a significant portion of the Arab populations in the Middle East), listing a series of genuinely anti-Jewish actions carried out on the international level, particularly by far-right forces nostalgic for the centuries-old “Jew hunt.” In short, Netanyahu managed to neutralize, at least internally, the effects of the general wave of solidarity with the Palestinians by transforming it into a re-edition of anti-Judaism. By leveraging the victimhood effect of those who feel persecuted by the entire world, he further united the domestic front and was able to thoroughly disregard not only UN interventions, which he openly and blatantly mocked, but also the “moderating” pressures from the U.S. presidency, which had already been weakened after Biden’s retirement and rendered even more fragile by Trump’s rise, who sided with Netanyahu and sought the Jewish vote for November.

Even the other weapon Sinwar relied heavily on—the protective “shield” provided in principle by the Israeli hostages—turned out to be blunt and added to the list of irreparable miscalculations already outlined. As time passed, the number of hostages dwindled, and the conditions of those few who were released turned out to be, as expected, disastrous, suggesting that those who remained in Gaza’s tunnels, if ever freed, would be in equally dire, likely irreversible physical and mental conditions. Thus, as the destruction of much of Hamas’s military structure was compounded by the successes of “high-profile” killings, most of the Israeli population’s attention towards the fate of the hostages diminished, leaving only the increasingly desperate and isolated pressure from the hostages’ relatives. The Israeli far-right had an easy time emphasizing that, ultimately, the hostages could not be given better treatment by the government than the hundreds of young Israelis killed in combat in Gaza since October 2023 and that they, too, should be regarded as war victims. Furthermore, it was even easier for the messianic extremism of significant sectors of Israeli society to remind Netanyahu of the now immensely unpopular (though at the time it was positively received by the majority of Israelis) exchange in 2011, promoted by the Israeli leader seeking a popularity boost, of a thousand Palestinian prisoners for one Israeli soldier, Gilad Shalit, held captive in Gaza. Among those thousand prisoners was Yahya Sinwar, the future supreme leader of Hamas, along with several other fighters from the organization, who, once released, resumed military activities, many of whom participated in the massacre on October 7 and were subsequently hunted down, with many becoming victims of Israeli army and intelligence services’ targeted killings.

Consequences and prospects

What remains to be assessed are the consequences of Sinwar’s death not only on the Israel/Palestine conflict but also on the broader balance of military conflicts in the Middle East. A newspaper headline, following the death of the Hamas leader, captured his role in this way: “Hamas was an orchestra; Sinwar turned it into a solo show.” Indeed, in just over a decade, Sinwar gained an immovable and unprecedented centrality within Hamas, in my opinion even surpassing that of Nasrallah for Hezbollah or Khamenei for the Iranian regime. And not so much for the charisma of a personality, as intransigent as ruthless, always at the forefront of military confrontation and systematic hatred for Israel, never abandoning the Gaza front, even brutal (the epithet “butcher of Khan Younis” was reportedly not attributed to him by the Israelis but by the Palestinians themselves due to his practice of personally torturing and killing alleged traitors and/or Israeli collaborators). Rather, his role was more about a long series of innovative and strategic insights that, within a few years, elevated Hamas’s influence throughout the region. Even before his release from Israeli prisons in 2011, Sinwar had already managed to find the right channel to initiate, as a representative of a Sunni organization, an unexpected alliance with Iran, the dominant country of the Shia world. He was the creator of the indoctrination project for young students, for whom he invented study camps to educate them in hostility and hatred towards Israel; more broadly, he was the architect of a largely successful attempt to identify Hamas with the population of Gaza, connecting every citizen with the militant organization by addressing not only military and political matters but also social welfare, ideological and cultural education of Gaza’s inhabitants, with the aim of binding them closely and irreversibly to Hamas. This led to unprecedented levels of recruitment and military training, involving most citizens in the conflict with Israel, either through warfare or as victims. Finally, he was the architect of the strategic project culminating in the massacre on October 7, which abruptly changed Hamas’s role not only in Palestine but on the global stage. As Michael Milshtein, one of the top Israeli experts on the Palestinian world, wrote: “Sinwar is a radical, an extremist, far from any compromise, seeing himself as a modern-day Saladin. But that doesn’t mean he doesn’t pursue realistic goals: he knew well that October 7 wouldn’t destroy Israel. In fact, that wasn’t his aim; he wanted to destroy the Jewish State’s self-confidence, fracture Israeli society, and break its internal pact, ending the dialogue on coexistence.” This was achieved because Sinwar—perhaps his greatest success—had managed to make Netanyahu and Israel’s political and military leadership believe that Hamas was no longer a mortal danger, providing a paradoxical image of an organization supposedly willing to abandon its plans to destroy Israel. “When we talk about an intelligence failure,” Milshtein continues, “we are talking about the failure of a view based on the false image that Sinwar managed to create, which influenced the way Israel made political and military decisions… He was mistaken for someone with whom negotiations were possible. He was skilled in crafting this image of a leader attentive to politics.”

However, despite this unprecedented centrality and indispensability within an organization that had operated for years like an “orchestra,” thinking that Sinwar’s killing is enough to dismantle Hamas, leading to its disappearance or at least marginalization, seems unrealistic. Personally, for years I have believed that the only hope for a positive future for the Palestinians lies in the end of Hamas’s hegemony over the Palestinians and of Netanyahu and the far-right over Israel. Yet the international evaluations among commentators and experts on the effects of Sinwar’s death and the drastic reduction of Hamas’s military forces (among the over 40,000 victims of the Gaza massacre, various observers estimate that at least half were Hamas fighters, meaning the group has lost about 60% of its militants on the ground) seem overly optimistic (for those who, like me, believe that this bilateral marginalization is fundamental for finding a way out of the conflict) and ultimately “comforting” and illusory, at least given the current state of affairs. While it is true that Sinwar’s figure does not seem reproducible, and his death is even more detrimental to Hamas than Nasrallah’s would be to Hezbollah or Khamenei’s to the Iranian dictatorship, the extreme centralization imposed by Sinwar (which was also intended to affirm the centrality of those remaining in Gaza fighting on the front lines compared to leaders in more comfortable positions in Qatar or Turkey) was the exception, not the operational rule of Hamas. Hamas was designed, on the contrary, not to give the enemy precise reference points, with various command centers, large or small. Several mid-level leaders remain relatively safe, far from Gaza, and generally well-protected (the killings of Ismail Haniyeh in Tehran and Saleh Al-Arouri in Beirut are not the norm), where they gather most of the funding and weapons and maintain contacts with state and non-state sponsors and supporters. These external bases have allowed Hamas to live and thrive in Gaza, and, based on what various international analytical sources suggest, they are still largely operational. As for the combatant forces on the ground, while the losses have been heavy, it is also true that there seems to be no credible alternative to Hamas’s dominance on the ground, making it not impossible for the internal structure to partially rebuild itself once the intensity of bombings and massacres diminishes.

On the other hand, the marginalization of Netanyahu and the far right in the Israeli government seems even more unrealistic, at least for now. I have the impression that many assessments regarding the developments of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict fail to take into account the key fact of recent weeks: that the conflict has extended far beyond the borders of Israel and Palestine and has spread, seemingly irreversibly, not only to Lebanon but also threatens Syria, and is on the verge of reaching what would be its focal point, posing immense destructive risks even beyond the Middle East. This focal point is the direct confrontation between the two key enemies, Israel and Iran, a prospect that Trump’s potential victory in the November elections could make even more explosive in the near future. In such a geopolitical context, I would be truly surprised if Netanyahu, who, apart from the hostage recovery, has achieved much of the goals he set out (with the three “high-profile” assassinations even more than the massacres in Gaza and the destruction of much of Hamas’s military apparatus), were to be sidelined and replaced.

Furthermore, returning to the epicenter of the past year’s war, the explosive and unresolved issue remains: who will manage Gaza and the West Bank, and how? Since I first started actively participating (now well over half a century ago) in mobilizations supporting the Palestinian struggle, I have always written and said that the “two peoples, two states” solution seemed fragile and very difficult to achieve positively, due to the imbalance of forces between the two potential entities. And that, though seemingly idealistic and futuristic, the best prospect, at least in principle, would have been the evolution of Israel into a secular, multicultural state, open to all ethnic and religious groups (not just the Jewish and Palestinian ones, but also the Arab/Islamic population, which, at present, counts at least as many citizens as the Palestinian population) and endowed with inclusive democratic institutions. Obviously, such an evolution appears far-fetched at the moment, but even the two-state solution, federated or not, no longer seems realistic or achievable. Thus, at present, there seems to be no solution in sight that could ensure not only military pacification but also the recognition of the fundamental rights of the Palestinian people.

In conclusion, the killing of Sinwar does not seem to be the event that will bring the conflict to an end, but rather just one stage—albeit a highly significant one, a “station”—crucial but neither decisive nor conclusive, in a military ordeal that is not likely to end but instead threatens to reach even greater levels of tragedy and explosiveness.

Piero Bernocchi